JULY-AUGUST 2024 Grief as a Medical Disorder

Thinking about Grief (and Other Emotions) as Medical Disorders

Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted. (Mat 5:4)

One Year to Mourn

Should grief be considered a Medical Disorder?

Paul Lauritzen, Mathew A. Crawford

Paul Lauritzen is emeritus professor of theology and religious studies at John Carroll University.

Interested in discussing this article in your classroom, parish, reading group, or Commonweal Local Community? Click here for a free discussion guide:

"In March 2022, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) announced a revision to its widely influential Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. The revised manual, known as DSM-5-TR, included a new diagnostic category: prolonged grief disorder (PGD). The announcement ignited a firestorm of controversy.

The criteria for categorizing PGD, for example, are very clear. For an adult who has had someone close to them die, PGD can be diagnosed if, after a year, they exhibit intense yearning and/or longing for the deceased or a preoccupation with thoughts or memories of the deceased.

In addition, diagnosis requires that at least three of the following symptoms be frequently present since the death of the deceased and every day for the month prior to diagnosis: identity disruption, a sense of disbelief about the death, avoidance of reminders of the death, intense emotional pain, difficulty reintegrating into everyday life, emotional numbness, a feeling that life is meaningless, and intense loneliness.

No clinician views grief itself as an abnormal human response to loss. Labeling some kinds of grief as a disorder is simply a recognition that grief can take on an unhealthy form that may require psychiatric intervention. The DSM revision does not designate all grief as a disorder; rather, it sets the criteria for disordered grief."

Problems Caused by Labeling a Person with a Diagnosis

Classifications that we assign to people are not neutral labels. Classifications affect the people classified. They may begin to see themselves in novel ways and begin to behave and interpret their behavior in accordance with the new label. This leads family members, friends, coworkers and others to also view and interpret their behavior with this new label. These labels are not confined to the medical community, they enter into popular culture. People begin to diagnosis themselves and others, whether appropriately or inappropriately.

The popularization of these categories may reshape how many will grieve: the pathologizing of loving bonds at the heart of grief and, in turn, a medicalized goal of weakening or severing these bonds instead of integrating them into a better future for those grieving may occur.

One important strand of thinking about grief embedded in the APA diagnosis is that grief is a kind of post-traumatic stress disorder related to an unhealthy attachment to a deceased loved one. The emphasis on the symptom of “yearning,” for example, highlights the conceptualization of grief as a disordered attachment.

In addition to the way individuals come to see themselves as suffering from a condition that must be treated, physicians begin to search for treatments to address new disorders. Pharmaceutical companies develop drugs to treat new conditions and then work to persuade patients and physicians of the need for the newly developed “treatments.”

In the end, there are both benefits and harms of conceptualizing grief as a medical problem. Thinking of grief as a psychiatric disorder will almost certainly promote a view of bereavement as an individual problem, not a communal one. But not recognizing debilitating long-term grief as a disorder may place obstacles in the path of those who do indeed need medical help.

ARE WE MEDICALIZING OUR EMOTIONS?

Statista: Mental Health the Top Health Concern

by Anna Fleck,

Oct 10, 2023

A 2023 Ipsos survey has found that mental health is now the chief health concern among U.S. adults, surpassing the coronavirus, obesity and cancer.

As the following chart shows, 53 percent of U.S. respondents said that they thought mental health was the biggest health problem facing people in their country as of August this year, up from 51 percent in 2022. Where the coronavirus had been considered the biggest health problem by roughly two thirds of U.S. respondents through the pandemic, perceptions of the danger of the virus have now curtailed to just 15 percent of respondents considering it the most serious health issue - lower than the rates for obesity (30 percent), cancer (29 percent) and even stress (18 percent).

According to the survey data, this trend is not unique to the U.S. Across the 31 countries polled by Ipsos as part of the Global Health Service Monitor, an average of 44 percent of people said that mental health was the top health concern facing their country. This was followed by cancer (40 percent), stress (30 percent), obesity (25 percent) and drug abuse (22 percent).

Sweden and Chile stood out for reporting particularly high levels of concern around mental health in 2023 (at 67 percent and 66 percent, respectively). Meanwhile, cancer was the most cited health concern in India (59 percent), obesity in Mexico (62 percent) and stress in South Korea (44 percent).

You will find more infographics at Statista

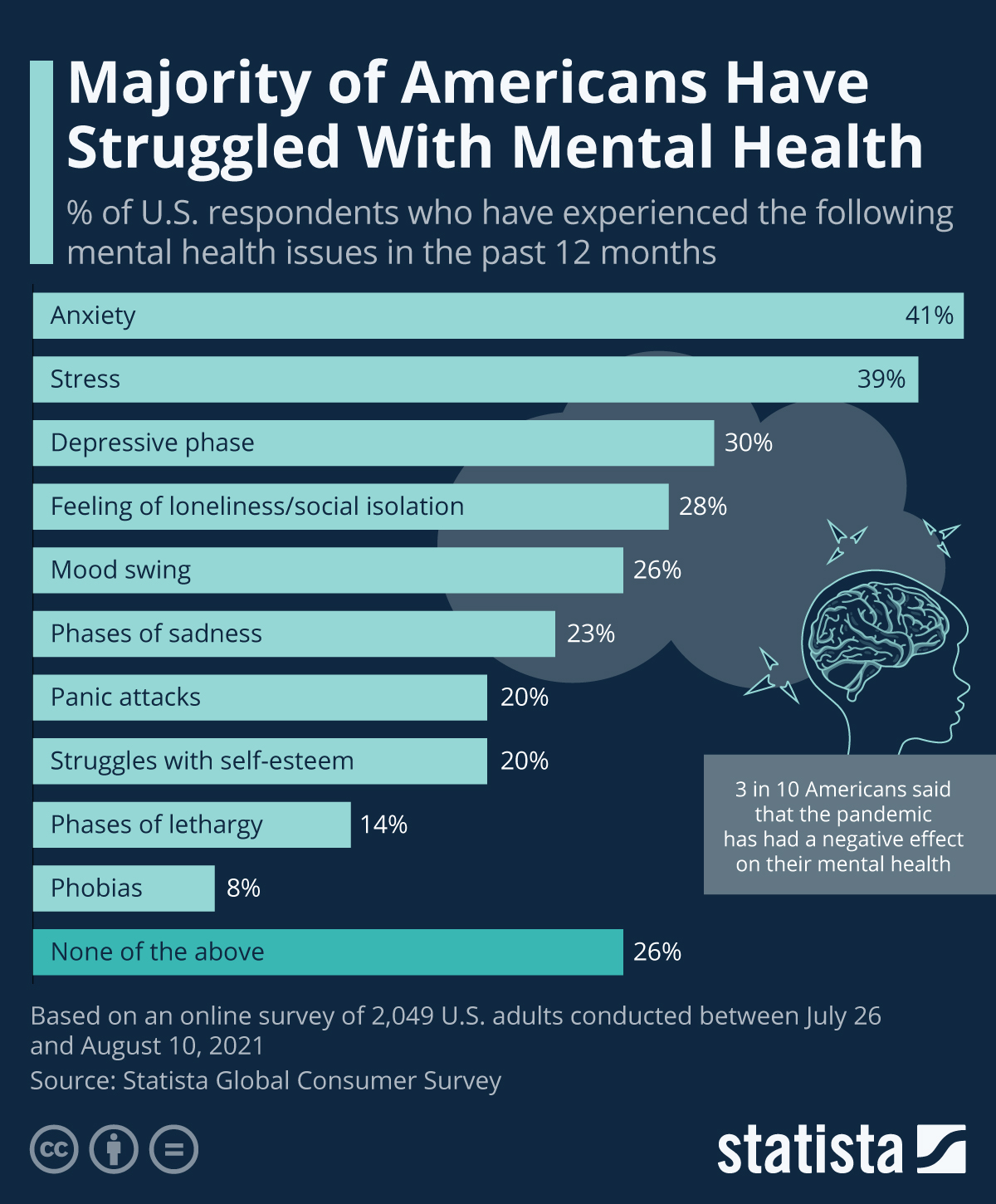

You will find more infographics at StatistaSTATISTA; Mental Health Issues in the United States

by Felix Richter,

Apr 30, 2024

Having long been stigmatized as a sign of weakness, mental health problems have become much less of a taboo in recent years.

The pandemic, with its unique set of challenges, accelerated that trend, as it not only caused a spike in symptoms of anxiety or depression, but also led to more people opening up about their problems.

In a recent Statista survey, 3 in 4 American adults reported that they have struggled with mental health in some form or other in the 12 months preceding the survey, making an open discourse about mental health issues all the more important.

According to the findings from Statista Consumer Insights, 52 and 49 percent of U.S. adults have experienced stress or anxiety in the past year, respectively, up from 46 and 38 percent in 2019. 29 percent of respondents reported having felt loneliness or social isolation in the past year, while 34 percent stated that they have gone through a depressive phase. Just 22 percent of respondents reported not having experienced any of the issues listed above, underlining how common mental health issues really are.

You will find more infographics at Statista

You will find more infographics at Statista

Comments

Post a Comment